Why your security policies are a business liability and what to do about it

Why your security policies are a business liability and what to do about it

I’ve been having quite a few conversations lately along these lines, making a case that many (if not most or all) of the security policies I’ve seen at organisations I’d categorise them as clear business liabilities.

I appreciate these are strong words and some of you must be thinking: “But, we need policies surely, otherwise Risk managing would be close to impossible and we wouldn’t meet any of the contractual or compliance objectives which help the business succeed right ?”

Well, right. I wouldn’t disagree with any of that. Where I have a problem is when the content of those same policies aren’t really based on any realisation of current state, future and what is currently being done to bridge the gap.

From experience, most security policies I’ve come across have something like ISO 27001 as its baseline, and the way most Compliance professionals approach the problem is the way I’ve been taught in my own ISO 27001 Lead Auditor course many years ago, which basically advocates for something along the lines of:

“You get ISO 27001, copy most of the information into documents but you ignore Annex 1. Then you go to the detailed guidance in ISO 27002 and you make those your control objectives as they’re clear and easily measurable”

There are 2 main reasons why I loathe this approach and why it’s a significant business liability which I’ll share next.

Blindness to gap leads to unfunded or inappropriate commitments

Security is rarely a profit center in most organisations. Most Execs will generally like to aim at doing the least amount of effort so Compliance is not a hindrance to organisational speed, and none of them got into business to be “Compliant”. That’s generally just something they have to deal with, but not a primary driver for what moves them, which is another reason why Senior Security people should NOT own Security policies. It should always reflect another Exec’s (depending on business could be a COO, CFO or anyone else) view of the risk appetite he/she has and the amount of situations he/she’s willing to risk manage or approve policy exceptions for.

So when we create and advise our management teams to adopt security policies which are based solely on uncontextualised references to best practices, we are creating a significant business liability because we just wrote on paper that all those best practices are “how and what we do” which to 99% of companies that’s very far away from your current reality.

So when we have auditors, regulators or customers seeking further assurances about how we manage security, we get bad situations we need to handle and it’s another “nail in the coffin” for any non-compliances. If you set the standard too high, you’re less likely to get people to voluntarily do the thing whilst at the same time reduce your professional credibility as someone who has no clue about the operational environment in which those policies should be applied, so no one will listen. Also, if that standard is too high and you know you’re generally far away from it, it implies that you’re choosing that any external validation of your security will be an immediate red flag and potential PR issue with the ensuing urgencies that accompany it, driving your focus away from dealing and treating strategic and systemic risk (as they won’t always overlap).

The ICO fine to DSG Retail recently included this exact situation where the report mentions that DSG “failed to adhere to its own policies in respect of access permissions and passwords”.

Collaboration is affected by tensions and conflict resulting from the gap between ‘work as imagined’ and ‘work as done’

This is probably the biggest strategic and systemic problem to blindly adopting best practices as internal policies. And is mostly about credibility and collaboration with the people to which security depends on to be effective. This is where we can lean on Safety II literature to help us assess our situation better.

This approach of unilaterally developing and signing off on security policies can be seen as a “mode for centralised control” of Security Compliance which, in Safety terms, is “old tech” which needs to evolve.

This centralized control approach refers to standardisation, generalisation and administration of safety management practices that are disconnected from the variability of the operational risks of the system or local unit.

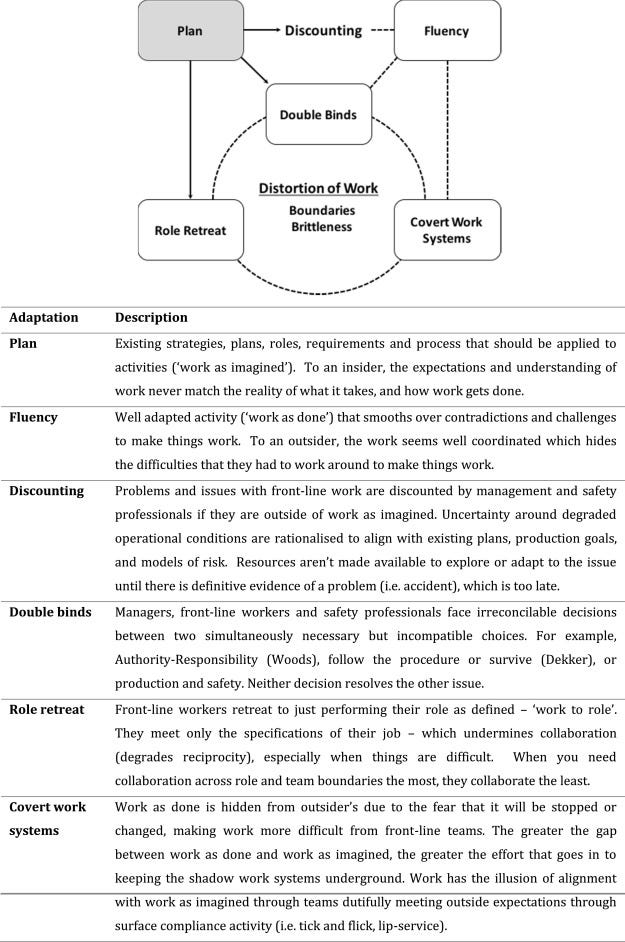

The image above is particularly telling about how and where we’re going wrong in Security Compliance. Let’s add some narrative to navigate it.

We, Security Pros, develop our Policies (Plan) as to how we imagine the work should be performed based on all those uncontextualised best practices. The first point of tension happens here, when the ones affected by policies internalise that the policy statements do not match the reality of how the work gets done or even what it takes to get it done.

So the policies are discounted by the ones affected by them, and some of the contradictions and challenges to make stuff work are smoothed out (Fluency) and no one gets any wiser about the emergent challenges in meeting policy. Whatever the current situation is, it’s rationalised as being appropriate because “this is how we do things”.

But then problems arise (Double binds) as front-line workers and the Security Pros “face irreconcilable decisions between two simultaneously necessary but incompatible choices” (this is where tension and conflict gets managed) which leads to either ‘Role retreat’ which is akin to being “Yes people” undermining real collaboration between teams and/or it leads to ‘Covert work systems’ in that work is hidden by front line teams afraid that it will be stopped or changed, and the wider the gap is between “Work as imagined” and “Work as Done” the greater the effort will go to keeping those practices hidden whilst providing the proverbial “lip service” to the Compliance requirements.

This type of approach leads to decreased collaboration between teams that should be supporting each other, and it doesn’t help that you get calls/email from Compliance when the wolf (auditors, yearly reviews, etc) are at the door demanding evidence.

Conclusions and alternatives

I’ve argued that the key challenges in developing and implementing security policies relate to organisational blindness caused by the ‘pretty words on paper’ vs the operational realities and constraints, and also that such approach undermines real collaboration by increasing tension and conflict between teams which are rooting for business benefits in their own expert domains.

Unfortunately, this isn’t just a matter of “have them review the policies and sign off on them” as we have decades of built in inertia and tension between departments and generally just a small expectation that policy will be met every time. We need to approach the problem in a completely different way.

I would suggest there are 3 things you can do not to fall victim to these challenges.

Compliance teams need to understand front-line work

Whether front line means Developers, Infrastructure engineers, Retail store sales staff or Facilities management, if you’re going to govern a part of your organisation you need to appreciate the operational challenges they face and reduce the size of the gap between “work as imagined” and “work as done”.

If your Compliance teams aren’t spending at least 15/20% or their time with front-line and ideally being trained in front line functions to fully appreciate constraints and tensions, then it’s unlikely that your policies are being met or that they are rooted in an understanding of your operational environment and the choices front line need to do on a daily basis. Unfortunately, a lot of Compliance/Risk teams still mostly live behind the screen and keyboard.

Once you appreciate the work being done with the resources and budgets available (money and time), then we can start having decent conversations about a) the best way to improve control environment b) the foreseeable operational challenges of meeting policy and c) determine potential alternatives or mitigating controls rooted in the operational reality

Query your IT environment before setting policy

If you have hundreds or thousands of systems in place, across a bunch of legacy and state of art systems, I understand it’s challenging to understand systemic challenges. But in 2020, you have combinations of open source and commercial tooling that can help you determine compliance across your estate (whether Cloud and/or On-prem). Understanding throughout your environment the different “pockets” of Compliance and having tailored policies which consider current capabilities and behaviours and every year slightly increases the mark for what Compliant is, is the best strategy for developing policy as it puts you in the position of a) understanding work as done and b) determine control strength which can then lead to informed decisions about how far off from current state your policies are from being met and if that’s an acceptable business liability in the interim. The problem is only when you don’t know how far off you are.

Base policy and control objectives on outputs of formal risk assessments or threat models

Your policy statements should not be based on security standards, but on risk assessments that were performed understanding your operational and regulatory/compliance environment.

There’s no problem in using security standards as the basis for a risk assessment, just don’t use as the basis for your policy statements and policy structure because that leads to perverse outcomes as we discussed.

Doing risk assessments and/or threat models with front-line staff (not necessarily their managers) not only involves them in the process so they’re more likely to support and contribute but collaborating in determining compensating measures are the pinnacle of effective collaboration when it comes to policy development.

This approach ensures that you’re only dealing with relevant threats, developing poliy statements which address a real business front-line challenge.

Your policies are then likely to be viable, shorter and addressing your particular operational needs.