Security for the 2020s: Addressing the Management Problem

Security for the 2020s: Addressing the Management Problem

“There is too much spending on the wrong things. Security strategies have been driven and sold on fear and compliance issues with spending on perceived rather than genuine threats” Art Coviello, RSA Chief Exec (2017)

“No one ever got fired for spending their budgets according to Gartner’s magic quadrant” Mario Platt, (Yes, I just quoted myself)

A big part of the challenge for security in organisations into the 2020s is Management related, and by this I mean the Security leaders themselves.

I believe this is happening due to the evolution of of technology itself (in which we’re increasingly seeing secure defaults, DevOps itself which is integrating security into their practices, and Cloud native security capabilities becoming more mature and readily deployable without multi-year transformation projects than their product-based alternatives) which is changing the nature of the Security leader’s budget, the realisation that old security paradigms are no longer fit for a complex world requiring quick experimentation and scale and the elevation of the role of the Security Leader in the organisational structure which means that security expertise is no longer enough to sustain someone in the role and management practice and theory are key to to retain talent and integration of security into corporate practices.

Budgets are changing

As we move towards a Cloud Native world, and as our organisations adopt more resilient design patterns focused on designing for Distributed, Immutable and Ephemeral systems most of the security solutions we have in our organisations (which focus on Confidentiality, Integrity and Availability) are not only ill-suited but add unnecessary overheads, actually conflicting with the attainment of business goals.

For the most advanced organisations, if I know my servers have a lifetime of 7–10 min and are then brought down, how far should I go in securing them ? Does that even make sense ?

Most security vendors operate in the “Product space”, which in Wardley mapping terms means they’re high profit, with vendors achieving advantage through implementation/features and it’s (typically nuanced) differentiation.

As most of those capabilities become Commodities or Commoditised by the Cloud vendors and/or CNCF, it implies that by extension the nature of the spend will change as well.

We’re no longer looking at Product licences renewed annually for most, but either them being essentially free or part of the CTO/CIOs integrated Cloud bill as another computing service consumed and this has huge implications to how much money is in the CISOs budget.

Due to this, I believe the budget that the CISOs have complete autonomous authority to spend without it being an agreed alignment with CIO/CTOs will reduce immensely. I’m currently reading “The Unicorn Project” by Gene Kim and one passage really summarises and hits home on this issue:

“You go around automating QA, your budget shrinks instead of grows.

I’m not saying you’re stupid, son, but you sure don’t seem to understand how this game works!” The Unicorn Project

I’m hoping CISOs will start playing a different game, one that aims for integration of security into everyone’s practices and not as a bolt-on you add to what someone else built, but as it has budget autonomy implications, there will be inertia to change due to past-success and the budget game itself.

This is NOT a matter of competitive advantage, this is an existential change for our organisations (adopting resilient design patterns). They either do it or become obsolete/irrelevant and/or beaten on cost by competitors, so it’s our job to enable it and stop the tyranny of control, and what I fear is how much will be spent on the wrong stuff in this transition period and how much that will set back true resilient design patterns for organisations involved leading to future requirement to address the debt introduced.

Security leaders not being fired

This one is almost an extension of has a significant overlap with my previous section. There’s a lot of not-so-clear and it has become an almost self-fulfilling prophecy by now that the average CISO tenure is 17–18 months.

There’s an article though that I found quite interesting here and provides a view on the evolution of the role itself. I agree with most of it.

Dismissals seems to be “mostly centered about [an] inability to address risk to a satisfactory state and in an economical manner”. This relates a lot to my previous point on Product-led vs Commodity-focused implementation of controls and technology.

Another aspect mentioned is not “delivering practical solutions to these same problems”, and where I also believe that a big part of technological security work into the 2020s will be immutable Configuration Assurance and helping ensure Configuration Drift is kept at a minimum.

Where I disagree with the article is in its way it describes that “the role is almost a unicorn — technical but with people skills. Executive-level, but with project management capabilities. Laser-focused prioritisation, but with broad overview knowledge and understanding”.

Let me be clear, I don’t disagree with the words or that all of those are great things to look for in a CISO or Security leader. What I do disagree with is that we need to be out there looking for Unicorns (I generally dislike the expression as in my mind it conjures views of innate characteristics and not of a lifetime of focused learning), as that’s not a scalable strategy especially when the average tenure is 17–18 months.

If your hiring strategy for a CISO focuses on finding a Unicorn, then I’m afraid you’re about to find yourself selecting someone on the wrong end of the Dunning-Kruger effect and will likely be contributing to the average or below average CISO tenure.

The CISO or Security Leader for the 2020s needs to understand the direction of travel in technology and appreciate that integration is a powerful market force, and at a minimum a) be the type of person who knows how to surround him/herself of people better than him/her in a lot of what it takes to be successful at the role b) be the type of person who are comfortable being called out by their team when they’re the ones impeding progress and c) be committed to organisational and incremental learning

Jabe Bloom recently shared on Twitter an article from HBR that he asked all who worked with him to read from Chris Argyris here. The fact this is an almost 30 year old document and seems like it was written yesterday, is what I call proper scary but unfortunately where we are.

Applying Doctrine

Most CISOs I’ve come across went through the ranks in various security roles until they got their CISO role. This is a good thing, as it suggests an effort to keep growing and embracing new challenges.

What it may also mean, is a lack of formal management knowledge which is important to perceive some of the actual and mental models of peers in organisations or have at your disposal the tools to work on team cohesion, happiness and performance.

Again, I refer back to swardley and Wardley mapping, particularly on the subject of Doctrine, which can find out more about at LearnWardleyMapping.com

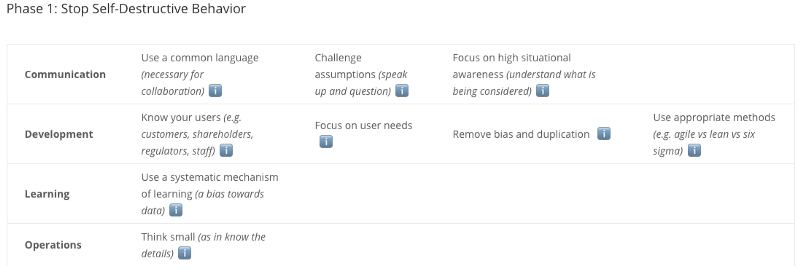

Most teams (not just security) are too much into self-harm and with practices which aren’t helpful for them or their organisations.

In order to not only be effective and efficient, but as or more importantly to be nice places to be, need to enable communication, development, learning and fully understand and appreciate their operations which is seldom the case.

Security leaders focusing on Doctrine and its different stages will create working environments where people strive and feel psychologically safe, allowing everyone to speak up and create continuous learnings. They’ll develop the right type of culture that is known to produce outstanding results and happier employees.

Embracing Complexity

A lot of security leaders, particularly those coming from a technical background, are good or even experts at Systems-thinking which has done a lot of good things for all of us over the years.

But Cognitive Sciences and the study of Complexity is emerging in the West as a series of framework which can help leaders make sense of their environments and ensure they treat problems according to their nature and not according to our preferred treatment or “problem preference bias”.

I’m making a general reference to Cynefin framework. A good part of what we do in security are Complex problems, as they imply the interaction between multiple agents (from technology, processes and people) and different types of constraints exist which affect them. A mindset of adopting Safe-to-fail experiments when multiple hypothesis exist as to “the right thing to do”, I believe, will be a key differentiator between the good and the best security leaders by fully considering context and linkages between the different agents.

Conclusion

There are many changes coming into the 2020s which will require significant paradigm shifts, and where old ways of doing things will become serious impediments to progress. As security leaders, we need to understand what those changes are and how they’re likely to affect not only our roles, but also how we manage and structure our teams to be truly business enabling and how we can continue the journey embed security into our organisations daily practices and rituals.